Words Pilar Viladas Photography Jason Schmidt

Published in No 12

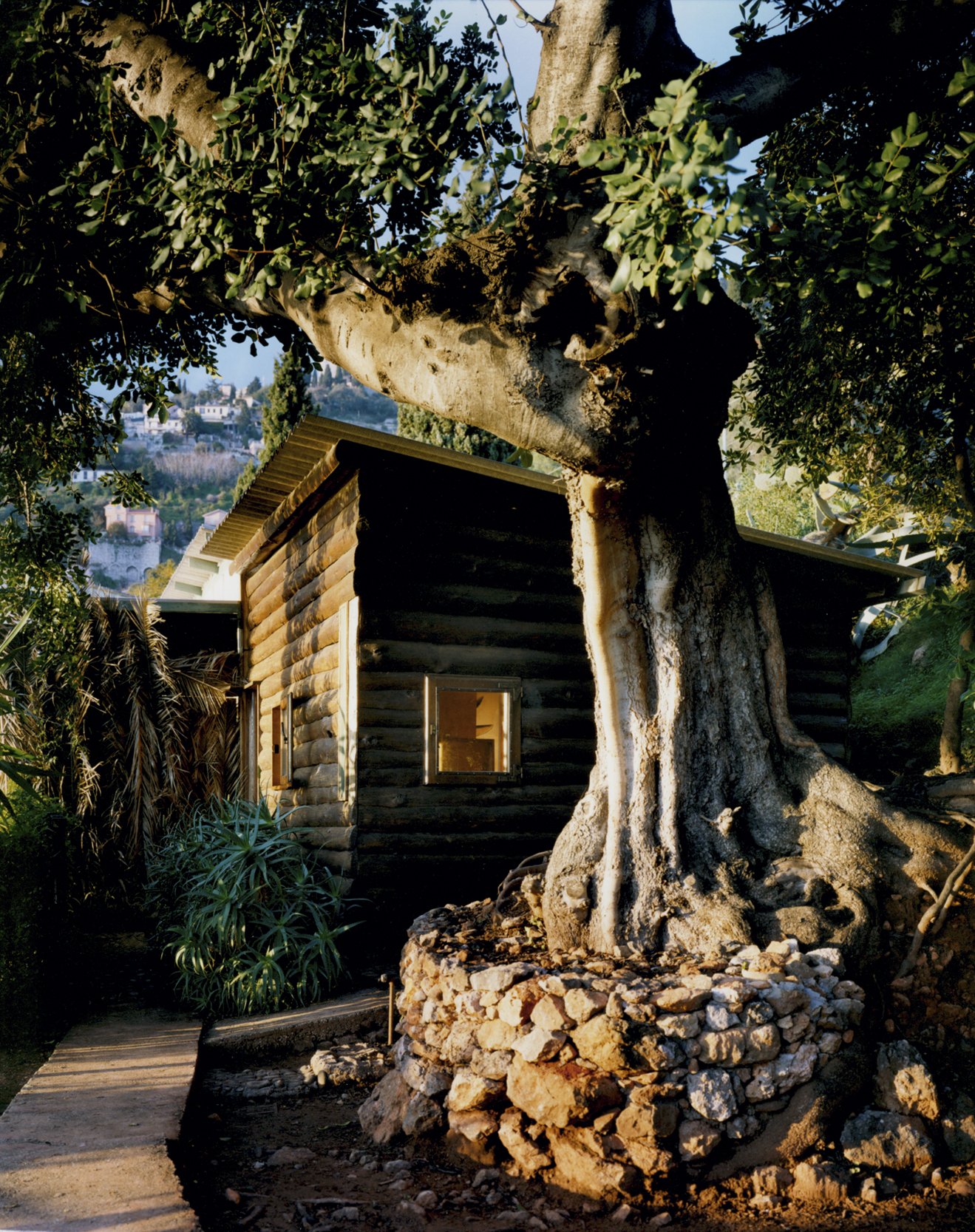

View of Cabanon and the garden.

Of all the projects I wrote about in my nearly seventeen years at The New York Times, one of the most memorable was the Cabanon, the tiny vacation cabin that the Modernist master Le Corbusier designed for himself in the early 1950s in Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, in the south of France.

The story, with its poetic photographs by Jason Schmidt, was published in the spring of 2001. I had seen many photographs of the architect’s sleek, white houses, like the 1929 Villa Savoye, and had visited his 1951 Notre-Dame du Haut chapel at Ronchamp, as well as the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts at Harvard — the architect’s only building in the U.S., which was completed in 1963. But the Cabanon intrigued me: why did this giant of the International Style want to spend his holidays in what looked just like a log cabin? (It was actually clad in umilled pine boards.) And a one-room cabin at that?

“Not a square centimeter wasted!” — Le Corbusier.

Le Corbusier wanted to design a dwelling that he called “a little cell at human scale where all functions were considered.” Well, almost all functions. The twelve-foot-square cabin had built-in furniture, including a table-desk, bookshelves, a single bed (which his wife, Yvonne, slept in, while her husband slept on the floor) and a wardrobe. There was a small sink near the desk, and a toilet — barely covered by a curtain — in a corner of the room. (As I wrote in the Times, Yvonne must have been a very patient woman; in their apartment in Paris, Le Corbusier put the bidet not in the bathroom, but in the bedroom, on full display. And while he adored his wife, he was also known for his roving eye.) There was no kitchen, because the architect took all his meals at the Étoile de Mer, a charming, small café (which is no longer open, but which is perfectly preserved) owned by Thomas Rebutato. Le Corbusier built the cabin onto one side of the café; he got the land as payment for designing a series of camping huts for Rebutato on the other side of the café). A door in the Cabanon’s entry hall opened directly into Mr. Rebutato’s quarters, so that the architect could slip in unseen for a meal.

Inside the Cabanon, warm plywood walls are punctuated by small, square windows — one of which frames a breathtaking view of the bay below, and Monte Carlo in the distance — with bifold wooden shutters that were, like the mural in the entry hall, painted by the architect, who was known for his paintings (more about that later). The space is elegant in its economy of line and materials, and indeed makes you think about how much space (a kitchen excepted) you really need to live in. Unlike most of the dwellings I’ve written about, this one was not going to produce dozens of images, but the ones that Jason took (assisted by Liz Shapiro), with their wonderful plays of light and shadow, still catapult me back there, twenty years later.

His wife Yvonne’s bed to the right. The toilet is seen behind the bed. Le Corbusier’s painting in the entrance.

My memories of the logistics of the trip have long since vanished, although I know I took a train to the town, perhaps from Nice. In order to get to the Cabanon, you have to walk down a long footpath, the Promenade Le Corbusier — not exactly the easiest way to transport photo equipment. But once you reach the site, you understand why the architect was so keen to build there. It’s close to the bay, and Le Corbusier was an avid swimmer. He once said that it would be nice to die swimming toward the sun, and he got his wish in 1965, at age 77, when he died of a heart attack while swimming in the bay.

Interior of the 12’x12’ cabin.

The cabin was a tightly orchestrated arrangement of built-ins, including a table / desk, bookcases, two beds, a wardrobe, a tiny sink and a toilet.

Since the shoot took relatively little time, Jason, Liz and I did a bit of sightseeing. We spent an afternoon in Monte Carlo, which provided an almost comical contrast to the monastic Cabanon, and we were also fortunate to be allowed to visit E-1027, the house — located down the hill from the Cabanon — that Eileen Gray completed in 1929 for the architect and critic Jean Badovici, who may have been Gray’s lover at the time. The house is now undergoing restoration, but at the time, its Gray-designed furnishings had been sold off at auction, and its interiors, in some places, were badly damaged by squatters. But there was another, more problematic alteration to the house: the murals that had been painted on the exterior in the late 1930s by Le Corbusier, a friend of Badovici’s. By this time, Gray and Badovici had parted ways, and she had built a house of her own, up the coast in Menton. But she was not pleased with Le Corbusier’s “improvement” on her work, and even today, there is something shocking about seeing these brightly colored, sometimes suggestive murals (which were deemed important enough to save, even though they were not original to the house) on the white walls, as if Le Corbusier felt compelled to leave his masculine mark on a building that was designed by a woman whose talent may have made him feel threatened. We also visited the grave that Le Corbusier designed for himself and Yvonne (who died in 1957), not far from the Cabanon. Inside a rather Brutalist shell, two colorful plaques bear their names and dates.

Breathtaking view of the bay below, and Monte Carlo in the distance.

I still think of the Cabanon, and how fortunate I was to be able to see it and write about it. It’s a contrarian’s house, meant only for working and sleeping, and not one I’d ever dream of living in. But the fact that Le Corbusier’s ideas were executed in a way that is both minimalist and tactile made a definite impression on me. Having visited, in my days as an editor, many houses that were exponentially larger and more opulent, but sometimes much less human, I wish it were the fashion to design a house starting with the idea of just enough. But don’t get me wrong: my dream house would have a kitchen. And a bathroom. With a door.

Pilar Viladas, a former design editor at The New York Times, writes about design and architecture.

Jason Schmidt is a photographer and director specializing in documenting artists and cultural figures, as well as architecture and interiors. His books Artists and Artists II were published by Steidl. He is currently at work on his first documentary. ba-reps.com.