Words Tony Moxham Photography Mattias Edwall

Published in No 14

In 1941, with the help of a close friend, Ralph Erskine built Lådan for his family of four in Sweden.

This story about one tiny home could and probably should be all about climate crisis. The reality of humans and housing, though, is more complex, so this is also a story about habit, power, comfort, and one little, old cottage in Sweden called Lådan.

Housing has been weaponized as a symbol of power since civilization. It goes this way … palaces are the homes of rulers, compounds are the homes of the elite, mansions are the homes of the rich, suburbs are the home to the middle class and, the poorer one is, the less private and the more shared housing becomes. Just over 20% of the world’s people literally have no home. In developed countries there’s a desire for big indoor spaces to accommodate extended family celebrations even if these spaces go unused for 90% of the time. At the higher end of this, people ask for houses with cinemas, nightclubs, lakes, basketball courts and pools with fireplaces in them — amenities common to public places. At the stratospheric end, there are single family homes with corporate amenities like fenced-off acreage, helipads, conference rooms, private research or care facilities, doomsday bunkers and animal menageries, which are surprisingly not a new thing. Mexico City’s Aztec elite, for example, built private palaces over reclaimed lakes they filled with human and animal oddities plucked from their own population; estates that monopolized local springs and water sources for monolithic bathing follies and pleasure gardens of unviable plants ripped from the furthest edges of empire. But until very recently in human history, home just meant shelter and was about meeting ideas of need and comfort before luxury.

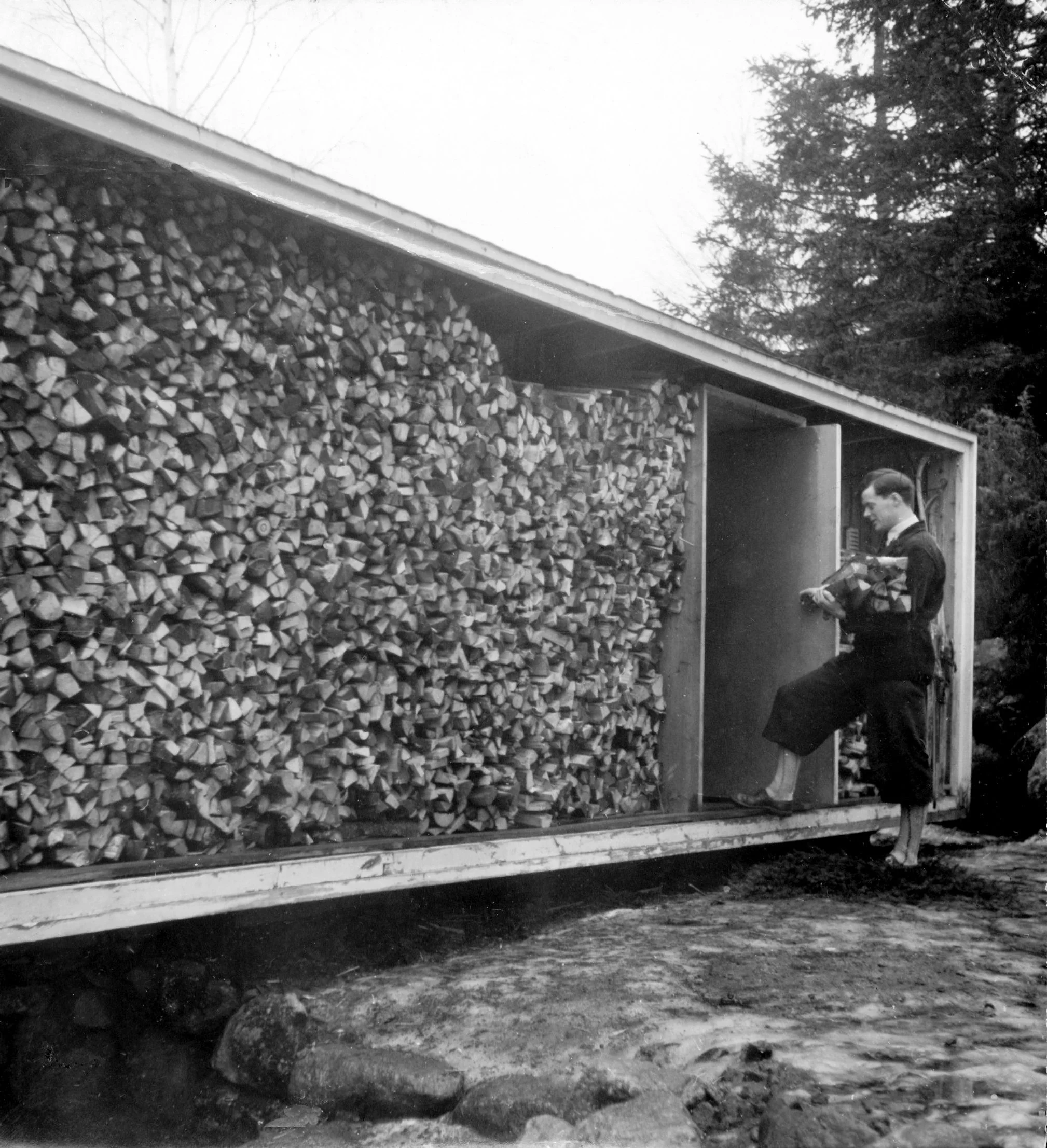

The extended roof on the north side provides space for firewood storage. The west and east facing walls, not seen, are painted red like a traditional Swedish cottage. Opposite

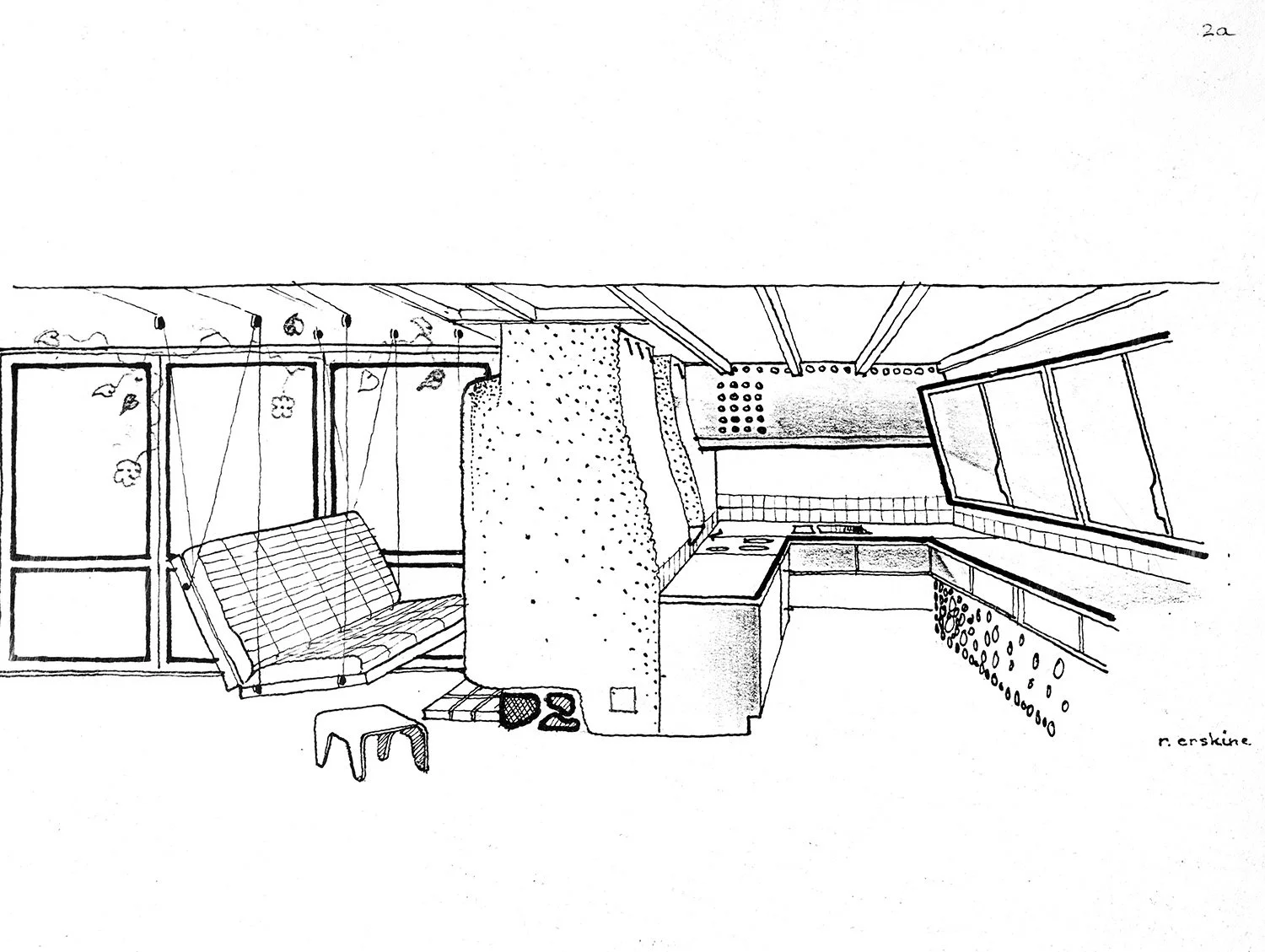

Archival illustration courtesy of ARKDES.

Erskine collecting wood. Archival photo courtesy of ARKDES.

Lådan is about comfort and encourages social interaction through its small size, like gathering in front of the fireplace.

“Lådan” translates literally as “The Box.” Ralph Erskine built it for his family of four in Sweden, in 1941, during WW2, with the help of a close friend. The house in the photos is a replica of the original, built in 1989, with Erskine’s participation and in a different location, but you get the idea. It’s a simple, rectangular wood frame, the exterior has two sides in vertical, natural wood paneling, and the other two sides are horizontal clapboard painted red, in the Swedish tradition, with a metal roof and a stone-veneer masonry chimney. What’s important about Lådan as a work of architecture and art is its focus on what’s necessary. The house captures a lot of what’s desirable about the tiny house movement: Lådan is seductive in its location, construction, restraint, and decoration. It’s visually utopian, which is nice in dystopian times, and its interior is very of the current zeitgeist.

Erskine himself was British, the child of socialist parents who raised him with a Quaker education that almost certainly affected his approach to architecture. He met his wife, Ruth, while at school. They moved to Sweden shortly before the outbreak of WW2 and never left. Ironically, one of his other achievements was the creation of what’s considered the world’s first modern shopping mall, the Luleå Shopping Complex of 1955, but that’s another story. What’s really cool about Lådan is what it proposes by what it excludes. It’s not really minimal, even at only around 20sqm (215sqft). Minimalism implies a certain restraint. Even though it’s got no bathroom or even plumbing (except for an outhouse), and water had to be carried from a well on the property, this home isn’t about monastic living or restraint. It encourages social interaction through its small size — a different means to the same end large homes try to accomplish with private cinemas and eight-oven catering kitchens — but with less implied social hierarchy and a lot less effort. Every nook, surface and view from within Lådan is about comfort. The space is divided between the kitchen and fireplace on one side and the living and sleeping space on the other. The building’s roof extends on the north side to provide firewood storage. That’s about it.

Erskin with his daughter. Archival photo courtesy of ARKDES.

Erskine at his desk. Archival photo courtesy of ARKDES.

Madeléne Beckman, who has the enviable position of Learning Curator at ArkDes, Sweden’s national center for architecture and design, is both Lådan expert and Erskine fangirl. She knows more than anyone about this exceptional home’s details and it’s a treat just to hear her talk about them. As she relates, “Ruth and Ralph went sailing for their honeymoon and were used to being on boats. Lådan is gigantic if you compare it to a boat, where you really have to manage a small space. Ralph took a few tricks from his sailing life, like the bed that can be raised, lowered, and used as a sofa. He also took a lot of knowledge about storage from boats.” The house’s cabinetry in the living and kitchen areas reflects maritime efficiency in design and simplicity. “The windows in the kitchen are quite small,” continues Madeléne, “but they capture the light and reflect it down onto the work surface — it’s a typical feature for Ralph Erskine we can see in a lot of his projects.”

The house’s cabinetry reflects maritime efficiency in design and simplicity.

Madeléne also explains the importance of the house’s site in regards to the home’s psychological size. With a lot of tiny homes, the land surrounding them becomes a psychological extension of the home itself and the space surrounding construction feels like an extension of the constructed space. “The amenities are very small,” Beckman concedes, “but with all that land around you, it makes things feel bigger. Because you’re so close to nature it really feels like you’re out there. Most of the Erskine’s social gatherings took place in the city. Privacy-wise, the children were very young, so I don’t think personal space was an issue. If you were going to have teenagers in that space it would have been more problematic, I guess, just going on my own experience with my own children (laughs). The plot itself was borrowed from a farmer, and they borrowed the farmer’s horse to transport construction materials. The reinforcements inside the chimney, for example, are made from the springs from an old bed.”

The way Erskine looks at housing through Lådan focuses on more primal needs and desires: a roof; warmth; a place to store and cook food; a place to feel safe with one’s family and enjoy their company; a place to sleep; and textural comforts you’re in contact with, one way or another, almost constantly while in or around the space. In that way, it functions more like a cave minus the mountain surrounding it than a free-standing structure. “The placement of the house works really well,” says Beckman. “It was on a south-facing hillside. It wasn’t built on the top because that’s the windiest part, and it wasn’t built down in the valley because that’s where the cold gets into a pocket. During the war, the winters were famously cold, but during warmer months they grew their own vegetables in terraced gardens, they had their own water, and they raised bees. I think there was a dog — a large dalmatian — and maybe some cats involved as well! In Lådan you can see a lot of things Erskine uses in larger projects later,” Beckman continues. “Because he was very interested in nature and climate, his work is very climate-friendly in its use of location and placement within the landscape, and he painted it partly red, like a traditional Swedish cottage. In Sweden we had a tendency to paint everything red because we wanted it to look like brick, which was much more expensive for most of 19th and 20th centuries. That accommodation of Swedish tradition is something he was excellent at — making good architecture with small means to create great livability. At the same time, he made Lådan something we’d never seen before.”

Learn more at arkdes.se/en

Tony Moxham's ceramic artwork for @MTobjects is represented by AGO-projects.com @AGOprojects

Mattias Edwall is based in Stockholm, Sweden. mattiasedwall.com @mattiasedwall