Interview Daniel Fuller Photography Martin Crook

Published in No 15

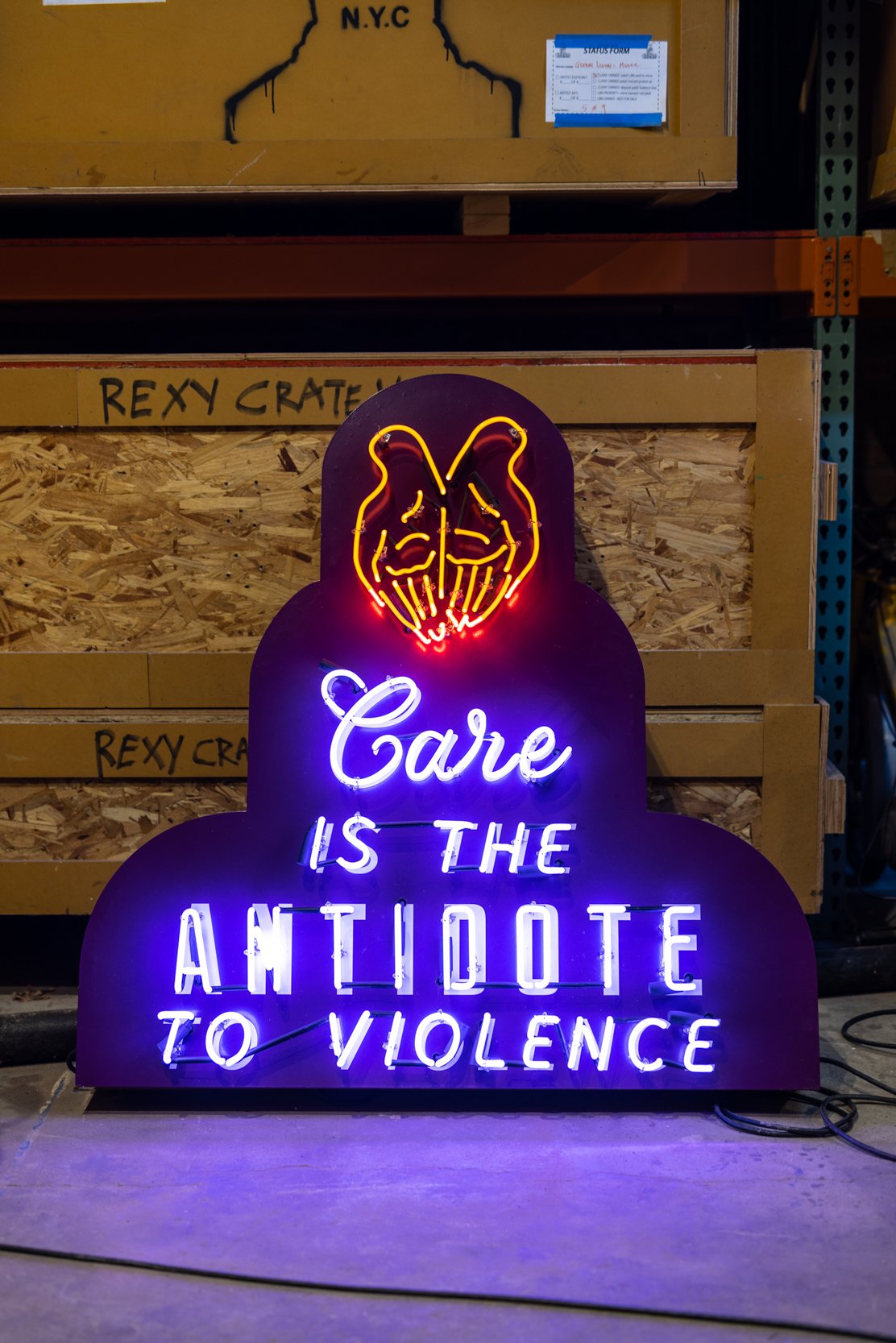

Matt Dilling with work by Demian Diné Yazhi for Forge Projects.

As luck would have it, when Matt Dilling and Lite Brite Neon Studio moved their operation to Brooklyn, one of their neighbors was Glenn Ligon, a true Mount Rushmore artist. Ligon's studio was upstairs from Dilling and, one day, he came down, and they started talking. He had never made a neon work and under different circumstances he might not have, ever. But this is what Lite Brite does.

They build bonds and a shorthand with artists. It’s a place where the studio can anticipate the needs of the artists, troubleshoot, and consider new possibilities. For Ligon's seminal sculpture, Warm Broad Glow, 2005, he envisioned the neon in black, glowing through the darkness, to represent his ideas on the volatility of time and identity. The studio had recently finished a commercial gig for Burberry, in which they painted the front of the tubes, allowing light to spill out from the back. Dilling described this practice as not unknown but not exactly common. But artists, as Dilling put it, "invite us to think differently about what we do." Ligon’s piece shines on the phrase "negro sunshine," pulled from Gertrude Stein's 1909 novel, Three Lives. The work is stunning. Unlike anything, I've seen before in a museum.

Another Country (After James Baldwin), 2017 by Glenn Ligon.

In 2015, the late curator Okwui Enwezor invited Ligon to create a neon for the Venice Biennale. It was set to be outside. According to Ligon, "What he didn't tell me was that what he meant by "outside" was a neon mounted on the facade of the central pavilion in the Giardini, the main exhibition space of the entire exhibition.” The piece, A Small Band, 2015, is a white neon sign fabricated by Lite Brite consisting of three words: blues, blood, and bruise. The piece appropriates a moment from composer Steve Reich's Come Out, 1966, in which Daniel Hamm of the Harlem Six convinced the police to release him, despite being accused of murder. It's a harsh reminder of the legacy of police brutality, presented front and center on art's grandest stage. Ligon said, "the neon I made with Matt has shown at Rebuild Foundation, in Chicago, The Pulitzer Foundation, in St Louis, and an exhibition copy of it is currently installed on the facade of the New Museum in New York. Each iteration of the neon was installed and overseen by Lite Brite."

Sam Reeder, a Neon Shop Tech.

Despite the accolades, perhaps the work Matt and Lite Brite are most known for comes from some of America's most challenging moments. While installing the Ligon neon at the Rebuild Foundation, in Chicago, Dilling came across the September 1955 issue of Jet Magazine, which first printed haunting images of Emmett Till in his open casket. He was lynched in 1955, at the age of 14, for speaking to a white woman. In 2008, the Emmett Till Memorial Commission began placing memorial signs to commemorate eight sites of significance in the murder. Almost immediately after their installation, the signs were stolen, shot, painted, tossed in the river, and blotted out with acid. The damage was repeated each time the signs were replaced. Perhaps the most significant memorial stands at Graball Landing, the "River Spot," which sits on the banks of the murky Tallahatchie River and observes where Till's body might have been pulled from the water.

The Emmett Till marker.

Tombstone encasement for Chairman Fred Hampton.

Over the years, the signs and replacement signs at this site have been riddled with more than 300 bullets, with people driving to this remote area specifically to commit a hate crime. National attention came, in 2018, when three white students from an Ole Miss University fraternity posted photos of themselves, smiling, rifles raised, on Instagram. As a sign maker, Dilling, who identifies as they / them, thought they could help. After two years of working with the Emmett Till Legacy Foundation to understand the site's needs, Lite Brite designed an industrial marker, a half-inch-thick steel sign sandwiched between three-quarter-inch Plexiglas panels. The new marker weighs over 500 pounds and is entirely bulletproof, sunk sturdily into the ground. This time, no one can eradicate history.

The Spring '22 exhibition, This Tender, Fragile Thing, at Jack Shainman's The School, in Kinderhook, NY, intertwined art and "non-art," young and less young, current news and vintage materials from the Black Panther Party to demonstrate how many concerns remain intact. Work after work did the almost impossible, wringing out as much grief as anger, as much pride as magic. The exhibition had no problem drawing lines and taking sides. With so many flashpoints, one inconspicuous work on paper, a collaboration between Dilling and their 8-year-old son, was somehow both modest and commanding: a back-and-forth wax or crayon rubbing pulled from an engraved gravestone. The quoted phrase was, "Let me just say: Peace to you if you're willing to fight for it." This gutsy and exquisite line was an excerpt from a speech Black Panther chairman Fred Hampton gave from the pulpit at the "People's Church," in Chicago's West Side in August 1969. Four months later, he was assassinated in his sleep by the police.

Dilling and Ziji, Mistress of Delight.

After the assassination Chairman Hampton was laid to rest in Bethel Cemetery, a rural burial ground near the Louisiana / Arkansas border. After hearing about the Emmett Till historical marker, the Hampton family reached out to Dilling, in 2019, as bullet holes have repeatedly damaged the Chairman's headstone. It's a big responsibility but Dilling has become not just the person to call for assistance in creating art that heals but also for creating protection for these memorials. In collaboration with Chairman Fred Hampton Jr., activist Akua Njeri and artist Jillian Van Volkenburgh, Dilling and the Lite Brite team created a box, a bulletproof shield, that now stands guard for the headstone. Made of steel, the front depicts Chairman Fred's laser-jet cut profile and beams of light from a crown. The back features the quote from which Dilling and their son created the rubbing. The words are very much alive. Sturdy, a little weathered, and particularly foreboding, the enclosure juts out beyond the headstone. The cut-outs reveal glimpses of the granite gravestone, hit, bruised, but standing firm and ready to fight when called.

This work has been a turn for Dilling, who’s been working as an electrician since the age of 12. In 1995, they were introduced to a Washington DC neon artist named Craig Kraft and began apprenticing in his studio. They made a formidable pair: Kraft trained as a visual artist, Dilling, the young electrician, assisting in many technical aspects of the art, welding and circuity. At the same time, a comprehensive retrospective of Bruce Nauman's work opened at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden. The works spanned walk-in environments, video installations, neons, one-liners, rhymes, and palindromes; this was a moment of sudden insight for a young artist. In 1997, he began operating his fabrication studio, early Lite Brite, from their dorm room at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. They would also sneak into classes at MIT, and much of Lite Brite's original equipment was culled from discarded gear from the campus. Slowly they built out the studio, adding equipment as needed when jobs depended on it.

Fragment for “The Gates to Times Square” 1966, by Chryssa.

Citational Ethics (Saidiya Hartman, 2017), 2020.

By 2001, the studio had moved to the Can Factory in Gowanus, Brooklyn, and began growing, taking larger projects, both artistic and commercial. Early on, Dilling was connected with the pioneering sculptor Keith Sonnier. Sonnier was a master of materials who began using neon to redefine drawing, having sketched with lights, colors, and architecture since 1968. This started a decades-long relationship.

Lite Brite certainly does one-off projects with artists, but one of the company's core values is the relationship. It is growing with an artist, understanding what is essential to an artist. As Dilling said, "It's a pretty intimate activity to produce someone's art. Our company has been significantly formed by the clients we've worked with and the projects we've engaged in."

In 2017, Lite Brite expanded beyond their Brooklyn home and opened a 15,000-square-foot wonderland in the former Kaufman Creamery and Ice Cream Factory in Kingston, NY. Art glows from every corner. I envisioned entering a dark room in the morning, flipping a single light switch, and watching the circus come to life. Even on a day off, the studio sings; it feels like a glorious and mysterious clubhouse, a place where important work gets done.

My admiration of Dilling stems from their having no ego as a fabricator. They have helped create works that will last as long as we have history books. They seem perplexed when I ask if they pine for a practice as a “solo” artist. They remind me that it's not separate, that Lite Brite’s hallmark is bringing their creative talents to everything they work on, that collaborating on other people's visions is as fulfilling, if not more, than creating one’s own. They summed it up nicely: "In many ways, I think our real gift in working on these projects is getting to make instruments for some of the greatest musicians, or participating in some of these incredible scores, historical scores."

I asked Dilling about the essential nature of the work they are helping put into the world. Running against the wind, trying to help in so many places. They took a moment then said, "There's this story about a guy walking along a beach after all these crustaceans had washed up. He was picking them up and throwing them back into the ocean. Someone else walking by asked, ‘Why are you doing that? There are thousands of these.’ He picked up another and responded, ‘It matters to this one.’”

litebriteneon.com

Daniel Fuller is a curator and writer based in Atlanta, Georgia. @fuller315

Martin Crook shoots for Tiffany & Co and Conde Nast Traveler, among many others. martincrook.co